Is Net-zero Transition by 2050 in Southeast Asia Possible?

11/15 2024

Author: Youngho Chang (Singapore University of Social Sciences)

Transition to net-zero implies that the amount of carbon dioxide emissions reduced or removed (sequestrated) at the sources can offset the amount of carbon dioxide emitted elsewhere in an economy. There are a few ways to decrease the amount of carbon dioxide emitted at the sources – reducing energy consumption, switching to less carbon-emitting energy sources and improving energy efficiency. Switching to less carbon-emitting energy includes producing hydrogen from no carbon-emitting sources or resorting to nuclear energy. All these options come with costs and affect the economy negatively. Apart from reducing the emissions of carbon dioxide at the sources, the carbon dioxide emissions can be removed or sequestrated. This also incurs costs and brings another question of where to put the removed carbon dioxide.

Carbon dioxide emitted is expected to stay in the atmosphere for about 150 or 200 years until it completely dissipates into a natural sink such as ocean (Nordhaus, 1994; Yin and Chang, 2020). This means that as long as carbon dioxide emitted is in the atmosphere, it contributes to radiative forcing, which is the main driver to increase the global mean surface temperature. Hence, achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 implies that the level of carbon dioxide emissions must peak by 2030 at the latest (Fankhauser et al, 2022).

ASEAN member countries have declared their pledges to achieve net-zero transition by 2050 through their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). A study utilizing the Low Emissions Analysis Platform (LEAP) presents various pathways for ASEAN member nations to achieve net-zero emissions. The study shows projections of greenhouse gas emissions and the costs of meeting the Paris climate goal (Handayani et al, 2022). However, this study does not consider how cross-border power trade in the ASEAN power sector affects the ASEAN member countries’ pathways to achieve net-zero emissions.

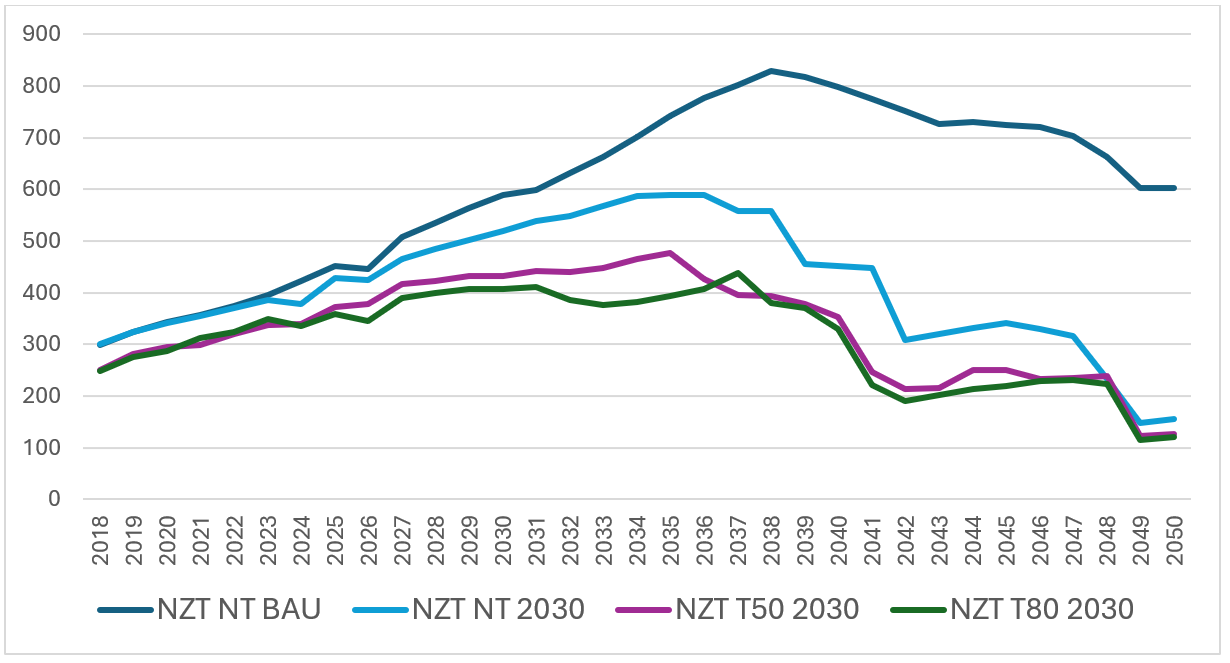

A cross-border power trade model examined whether ASEAN member countries have technological capacities to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 in the ASEAN power sector (Chang, 2024). The objective of the power trade model is to minimize the total cost of electricity generation from 2018 to 2050 subject to capital expenditure, operation expenditure, carbon emissions and costs, and cross-border transmission costs and losses, and various constraint conditions that ensure the cross-border power trade happen. The study employs four scenarios – Business-As-Usual as a reference scenario (NZT NT BAU), No cross-border power trade with emissions capped at the level of 2030 (NZT NT 2030), Cross-border power trade up to 50% of domestic demand for each member country with emissions capped at the level of 2030 (NZT T50 2030), and Cross-border power trade up to 80% of domestic demand for each member country with emissions capped at the level of 2030 (NZT T80 2030).

Net-Zero emissions by 2050 would require the level of carbon emission to peak around 2030 in the ASEAN power sector. But the level of carbon emissions in the ASEAN power sector appears to increase until 2040. The ASEAN power sector is endowed with huge potential of renewable resources such as hydropower, wind and solar. As figure 1 below shows, scenarios of cross-border power trade present the ASEAN power sector appears to achieve net-zero emission by 2050 at lower system costs compared to the scenario of no cross-border power trade (its figure is not shown here), which in turn supports that the ASEAN power sector has applicable power technologies and clean resources to achieve the goal by 2050. Among various renewable sources, solar PV and hydropower appear to be the key drivers to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 in the ASEAN power sector.

The outcomes of the cross-border power trade model clearly present cross-border power trade could help the ASEAN achieve net-zero transition by 2050 in a collective setting. However, the current state in the framework of cross-border power trade is not ready to realize possible benefits of cross-border power trade in the ASEAN. A few policy recommendations are drawn that would help the ASEAN power sector realize the possible benefits. First, it would be good to complete the planned cross-border interconnections in the ASEAN as early as possible. Second, it would be also good to accelerate integration of solar PV and hydropower into the power system of the ASEAN. Third, it would be imperative to develop transparent, fair and efficient frameworks of cross-border power trade in the ASEAN power sector.

Reference:

Chang, Youngho (2024), “Power Trade and Hydroelectricity Development in the Greater Mekong Sub-region: Perspectives on Economic and Environmental Implications, in Large-Scale Development of Renewables in the ASEAN: Economics, Technology and Policy, edited by Han Phoumin, Rabindra Nepal, Fukunari Kimura and Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary, Springer, pp. 55 – 77.

Fankhauser, S. and 14 authors (2022). The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nature Climate Change. Vol 12 (January 2022), 15 – 21.

Handayani, Kamia, Pinto Anugrah, Fadjar Goembira, Indra Overland, Beni Suryadi and Akbar Swandaru (2022). Moving beyond the NDCs: ASEAN pathways to a net-zero emissions power sector in 2050. Applied Energy, Vol. 311, 118580. Nordhaus, William. D. (2014). A question of balance: Weighing the options on global warming policies: Yale University Press.

Yin, Di. and Youngho Chang (2020). Energy R&D investments and emissions abatement policy. Energy Journal, Vol. 41. No. 6, 133 – 156.